Jellyfish are among the most ancient and fascinating marine creatures, ranging from deadly to completely harmless. Below you’ll find notable species and groups, each classified by their stinging potential—dangerous/venomous, light stinger, or harmless—along with habitat, appearance, venom detail, and an intriguing fact.

Jellyfish can be classified into several types based on their taxonomy and body structure. Here are the main types of jellyfish:

Post Contents

- Scyphozoa (True Jellyfish)

- 1. Moon Jellyfish (Aurelia aurita)

- 2. Lion’s Mane Jellyfish (Cyanea capillata)

- 3. Barrel Jellyfish (Rhizostoma pulmo)

- 4. Cannonball Jellyfish (Stomolophus meleagris)

- 5. Compass Jellyfish (Chrysaora hysoscella)

- 6. Pacific Sea Nettle (Chrysaora fuscescens)

- 7. Nomura’s Jellyfish (Nemopilema nomurai)

- 8. Blue Jellyfish (Cyanea lamarckii)

- 9. Upside-Down Jellyfish (Cassiopea andromeda)

- 10. White-Spotted Jellyfish (Phyllorhiza punctata)

- 11. Blubber Jellyfish (Catostylus mosaicus)

- 12. Crystal Jellyfish (Aequorea victoria)

- 13. Mauve Stinger (Pelagia noctiluca)

- 14. Cotylorhiza (Mediterranean Jellyfish)

- 15. Helmet Jellyfish (Periphylla periphylla)

- 16. Stygiomedusa & Deepstaria (Deep-Sea Jellies)

- 17. Crown Jellyfish (Coronamedusae)

- 18. Rhizostomae (Root-Mouthed Jellyfish – Group)

- 19. Semaeostomeae (Order – True Jellyfish)

- 2. Cubozoa (Box Jellyfish)

- 3. Hydrozoa (Hydrozoan Jellyfish and Siphonophores)

- 4. Staurozoa (Stalked Jellyfish)

- Additional Noteworthy Jellyfish

- Table: Quick Classification Overview

- Final Thought

- Citations:

🧬 By Classification (Phyla & Classes)

- Scyphozoa (True Jellyfish)

- Most familiar, bell-shaped jellyfish

- Includes moon jelly, lion’s mane jellyfish

- Cubozoa (Box Jellyfish)

- Cube-shaped, highly venomous

- Includes the Australian box jellyfish

- Hydrozoa (Colonial Jellyfish)

- Often small, some colonial like the Portuguese man o’ war

- Not all resemble classic jellyfish

- Staurozoa (Stalked Jellyfish)

- Sessile, stalk-like base instead of free-swimming bell

- Lives on ocean floors, cold waters

🌍 By Habitat

- Coastal Jellyfish – Found near shorelines (e.g., Sea nettles)

- Deep-Sea Jellyfish – Bioluminescent, live at great depths (e.g., Atolla jellyfish)

- Open Ocean Jellyfish – Drift through pelagic zones (e.g., Nomura’s jellyfish)

⚠️ By Venom Level

- Harmless or Mild Sting – Moon jellyfish, cannonball jelly

- Painful Sting – Sea nettles, lion’s mane jellyfish

- Dangerous/Deadly – Box jellyfish, Irukandji jellyfish

📏 By Size

- Small Jellyfish – Irukandji (~1 inch)

- Medium – Moon jelly, compass jelly

- Giant Jellyfish – Lion’s mane jellyfish, Nomura’s jellyfish (can be meters wide)

Scyphozoa (True Jellyfish)

These are the classic, large “true jellyfish” commonly encountered in oceans worldwide. They have a typical umbrella-shaped bell and long tentacles.

1. Moon Jellyfish (Aurelia aurita)

Classification: Scyphozoa

Habitat: Coastal waters worldwide; prefers temperate and tropical seas

Size: Up to 40 cm (16 in) diameter

Diet: Plankton, mollusks, crustaceans, small fish

Venom: Mild; harmless to humans

Moon jellyfish are easily recognized by their translucent, saucer-shaped bell and four horseshoe-shaped gonads visible through the bell. They pulse gently through the water and are often found in large swarms. Their short, fringe-like tentacles capture food which is moved to their oral arms. Though they possess venomous stinging cells (cnidocytes), their sting is too mild to harm humans. Moon jellies are important in marine food webs and adapt well to both natural and artificial environments, making them common in aquariums.

2. Lion’s Mane Jellyfish (Cyanea capillata)

Classification: Scyphozoa

Habitat: Cold waters of the Arctic, North Atlantic, and North Pacific

Size: Bell up to 2.5 m (8 ft); tentacles over 30 m (100 ft)

Diet: Zooplankton, small fish, other jellyfish

Venom: Moderate; can cause pain and skin irritation

The lion’s mane jellyfish is the largest known jellyfish species, named for its mass of long, hair-like tentacles. Its bell is often reddish-brown or yellow and divided into eight lobes. It drifts with ocean currents, paralyzing prey with its venomous tentacles. Though its sting is not deadly, contact can be painful. These jellies often appear in summer and fall in northern waters and are known to form large blooms. Their sheer size and long trailing tentacles make them a striking but dangerous presence.

3. Barrel Jellyfish (Rhizostoma pulmo)

Classification: Scyphozoa

Habitat: Northeast Atlantic, Mediterranean Sea, and coastal European waters

Size: Up to 90 cm (35 in) in diameter; weighs up to 25 kg (55 lbs)

Diet: Plankton, small fish, fish eggs

Venom: Mild; generally harmless to humans

Barrel jellyfish, also called dustbin-lid jellyfish, are named for their stout, dome-shaped bell. They have eight thick, frilly oral arms but lack long tentacles. Their bluish or pinkish translucent bodies often wash ashore in large numbers. Despite their size, their sting is mild and rarely causes discomfort. Barrel jellies are filter feeders, constantly moving to draw plankton-rich water over their mucus-coated arms. They play a role in the diet of leatherback sea turtles and other marine predators.

4. Cannonball Jellyfish (Stomolophus meleagris)

Classification: Scyphozoa

Habitat: Warm coastal waters of the western Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico

Size: Up to 25 cm (10 in) in diameter

Diet: Zooplankton, larvae, detritus

Venom: Mild; rarely causes irritation

Cannonball jellyfish have a dome-shaped bell resembling a cannonball, with brown or bluish bands and stubby oral arms. They are strong swimmers and often form dense aggregations. Known for their mild sting, they’re generally safe for swimmers. Their populations spike in summer, and they’re commercially harvested in Asia. Cannonball jellies help regulate plankton populations and are a favorite food for leatherback turtles. They are also known to host small crabs within their bells.

5. Compass Jellyfish (Chrysaora hysoscella)

Classification: Scyphozoa

Habitat: Northeast Atlantic, North Sea, and Mediterranean

Size: Bell up to 30 cm (12 in)

Diet: Plankton, fish larvae, crustaceans

Venom: Moderate; causes skin irritation

The compass jellyfish is named for its bell markings resembling a compass rose. It has 24 long tentacles and frilled oral arms. This species prefers shallow waters during warmer months and can often be seen near the UK and Ireland. It uses its tentacles to catch and immobilize prey. Though not dangerous, its sting can cause discomfort and redness in humans. It drifts with ocean currents and is part of a fragile but vital marine food chain.

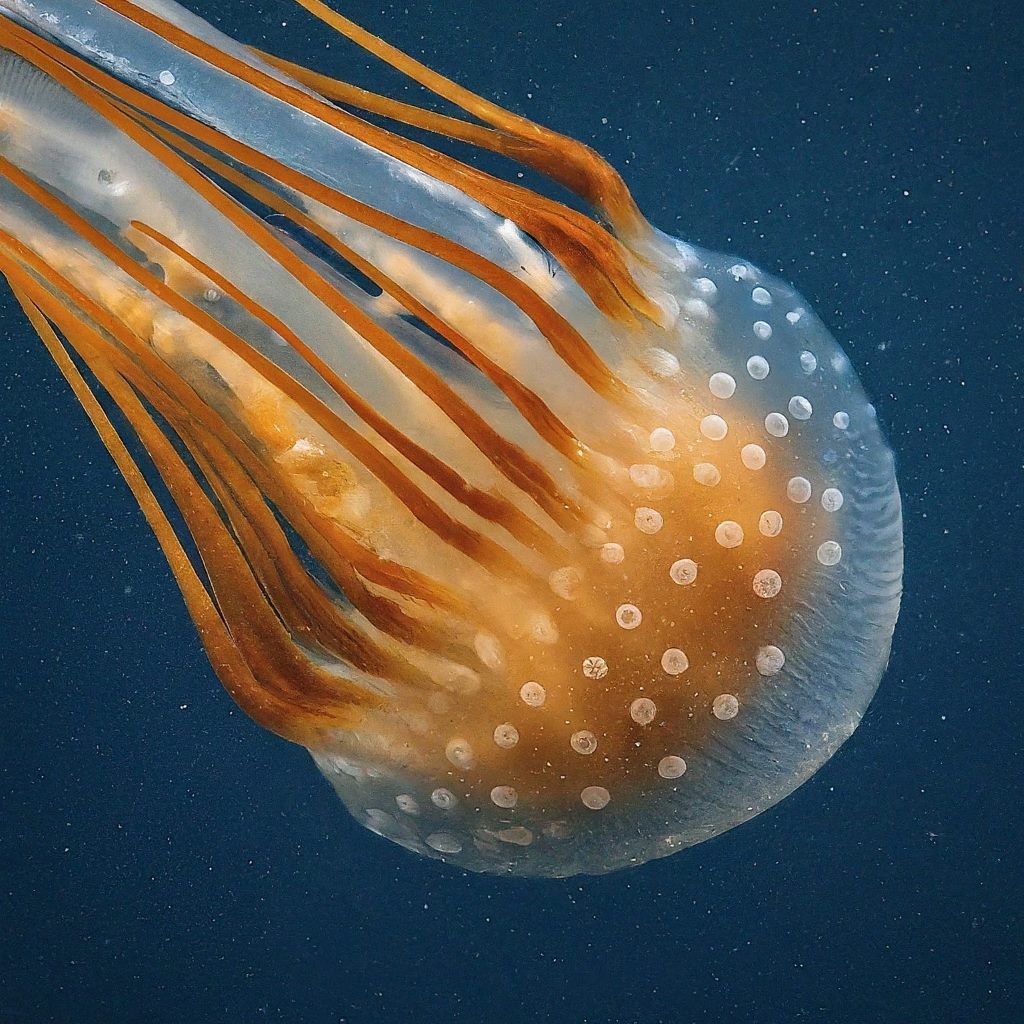

6. Pacific Sea Nettle (Chrysaora fuscescens)

Classification: Scyphozoa

Habitat: Pacific Ocean, from Canada to Mexico

Size: Bell up to 1 meter (3.3 ft); tentacles up to 4.5 meters (15 ft)

Diet: Zooplankton, small fish, other jellyfish

Venom: Moderate; causes burning sensation

The Pacific sea nettle has a golden-brown bell and long maroon tentacles. It moves rhythmically through coastal Pacific waters, using its trailing tentacles to capture prey. Its sting can cause pain, redness, and itching. These jellyfish often form blooms, which can affect fisheries and power plants. In aquariums, they’re a visual favorite due to their graceful pulsations. Despite their sting, they play a key ecological role by feeding on overabundant plankton and small fish.

7. Nomura’s Jellyfish (Nemopilema nomurai)

Classification: Scyphozoa

Habitat: Coastal waters of China, Korea, and Japan

Size: Bell up to 2 meters (6.6 ft); weight up to 200 kg (440 lbs)

Diet: Zooplankton, fish eggs, larvae

Venom: Moderate to strong; causes rashes, nausea

One of the largest jellyfish on Earth, Nomura’s jellyfish can reach the size of a small adult human. Its bell is tan to reddish-brown with thick, curtain-like oral arms. Seasonal blooms can disrupt fishing and tourism in East Asia. Its sting is painful and occasionally dangerous, especially in high concentrations. These giants drift near the sea surface and feed on large volumes of plankton. Despite their intimidating presence, they’re sometimes processed for food and cosmetics in East Asia.

8. Blue Jellyfish (Cyanea lamarckii)

Classification: Scyphozoa

Habitat: Northeast Atlantic, North Sea, Irish Sea

Size: Bell up to 30 cm (12 in)

Diet: Zooplankton, fish larvae

Venom: Mild to moderate; may cause itching or rash

The blue jellyfish is known for its vivid bluish or purplish bell and trailing tentacles. Young specimens may appear more transparent. They’re commonly seen in coastal European waters, especially during summer. Although their sting isn’t dangerous, it can cause temporary discomfort. Blue jellyfish help control zooplankton populations and often appear in the same waters as moon jellies. They feed by ensnaring prey with their tentacles and drawing it into their mouth opening.

9. Upside-Down Jellyfish (Cassiopea andromeda)

Classification: Scyphozoa

Habitat: Shallow lagoons, mangroves, and mudflats in tropical waters

Size: Bell up to 30 cm (12 in)

Diet: Plankton and symbiotic algae

Venom: Mild; may cause tingling or irritation

Unlike typical jellyfish, Cassiopea lies upside-down on the seafloor with its bell touching the substrate and arms facing upward. This posture maximizes sunlight exposure for its symbiotic algae, which provide much of its nutrition through photosynthesis. They can release mucus containing stinging cells, which may irritate swimmers. Often found in calm, shallow waters, they are relatively passive and slow-moving. Their unique behavior and mutualistic relationship with algae make them fascinating to researchers and aquarium enthusiasts.

10. White-Spotted Jellyfish (Phyllorhiza punctata)

Classification: Scyphozoa

Habitat: Indo-Pacific; now invasive in Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean

Size: Bell up to 50 cm (20 in)

Diet: Plankton, small aquatic organisms

Venom: Mild; harmless to humans

White-spotted jellyfish are known for their translucent bell covered in white dots and bluish oral arms. Native to the Indo-Pacific, they’ve spread to other oceans and often outcompete native plankton-feeders. Though non-aggressive and safe for swimmers, their large swarms can clog fishing nets and intake pipes. They are filter feeders, consuming large amounts of plankton, which can affect local ecosystems. Their mild venom doesn’t usually bother humans, making them popular in public aquariums.

11. Blubber Jellyfish (Catostylus mosaicus)

Classification: Scyphozoa

Habitat: Coastal waters of Australia and Indo-Pacific

Size: Bell up to 35 cm (14 in)

Diet: Plankton, small fish, crustaceans

Venom: Mild to moderate; irritation possible

Blubber jellyfish have a firm, dome-shaped bell in shades of blue, brown, or white. Their short, club-like oral arms give them a rounded appearance. They are strong swimmers and often appear in large aggregations, especially after rainfall. Though their sting is mild, it can cause irritation in sensitive individuals. They are filter feeders, playing a key role in coastal food webs. In some regions, they are harvested for food.

12. Crystal Jellyfish (Aequorea victoria)

Classification: Hydrozoa (Leptothecata)

Habitat: Pacific coast of North America

Size: Bell up to 10 cm (4 in)

Diet: Zooplankton, small invertebrates

Venom: Harmless to humans

Crystal jellyfish are nearly transparent and known for their bioluminescence. They produce green fluorescent protein (GFP), which has become essential in biomedical research. Their bell is gelatinous and rimmed with hundreds of bioluminescent dots. They live in cold, coastal waters and feed at night. Though they have stinging cells, their venom is too weak to affect humans. These jellyfish have revolutionized science due to the isolation of GFP, which is now used in gene expression studies.

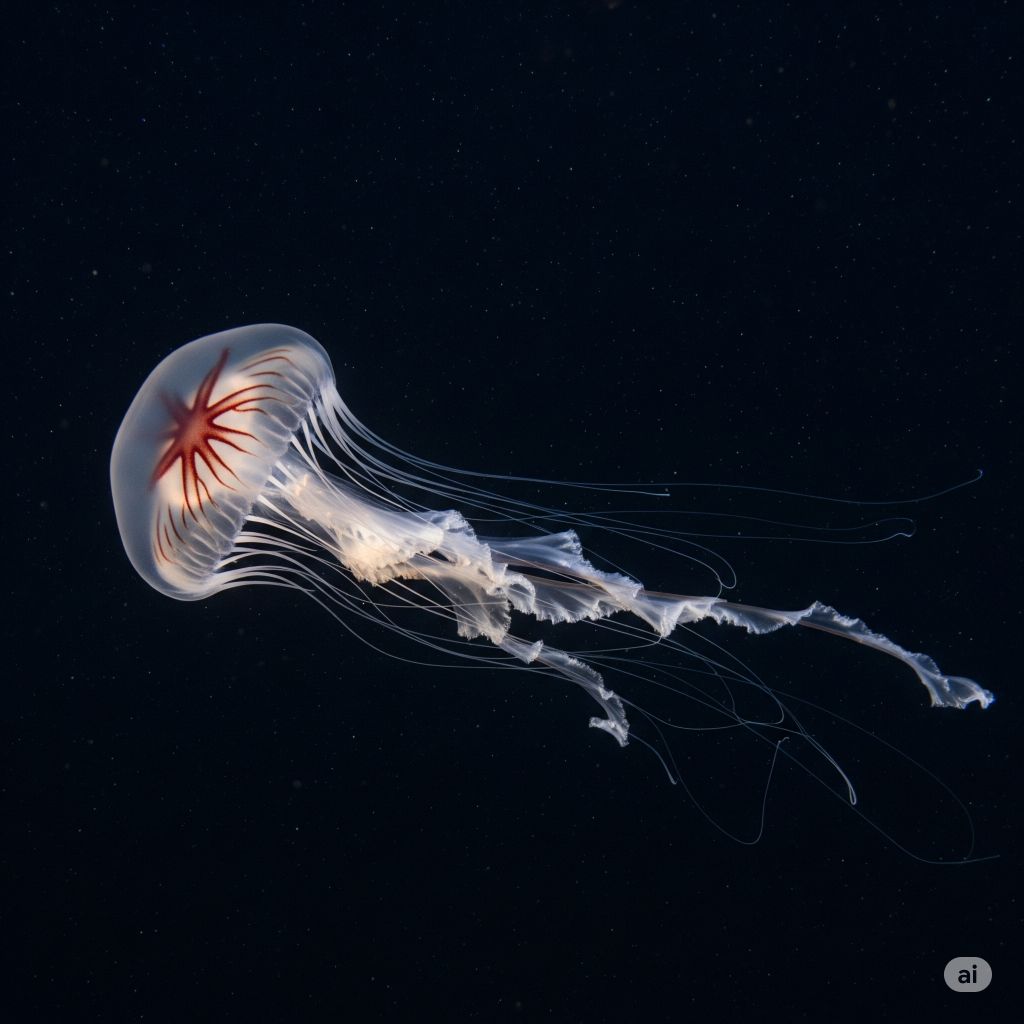

13. Mauve Stinger (Pelagia noctiluca)

Classification: Scyphozoa

Habitat: Open waters of the Mediterranean and Atlantic

Size: Bell up to 10 cm (4 in)

Diet: Plankton, fish eggs

Venom: Strong; painful to humans

The mauve stinger has a translucent purple-pink bell with glowing spots and long stinging tentacles. It’s highly bioluminescent and lights up when disturbed. This jellyfish floats in open waters but sometimes appears in coastal swarms, particularly in the Mediterranean. Its sting is painful and can leave welts, making it a concern for swimmers. Despite its small size, it’s one of the more venomous jellyfish in European waters. It plays an important role in the pelagic ecosystem.

14. Cotylorhiza (Mediterranean Jellyfish)

Classification: Scyphozoa

Habitat: Mediterranean Sea

Size: Bell up to 35 cm (14 in)

Diet: Zooplankton, algae (symbiosis)

Venom: Mild; harmless to humans

Cotylorhiza tuberculata, also called the fried egg jellyfish, has a yellow dome resembling an egg yolk. Its short, frilly arms host symbiotic algae that supplement its diet via photosynthesis. These jellies are common in summer and are often found floating near the surface. Their sting is extremely mild and generally safe for swimmers. They help maintain plankton balance and are studied for their unique algae-based symbiosis.

15. Helmet Jellyfish (Periphylla periphylla)

Classification: Scyphozoa

Habitat: Deep ocean, often below 1,000 meters

Size: Bell up to 35 cm (14 in)

Diet: Zooplankton, small invertebrates

Venom: Mild; rarely encountered by humans

Helmet jellyfish are deep-sea dwellers with a reddish, conical bell that resembles a medieval helmet. They are bioluminescent and rarely seen near the surface unless disturbed. These jellies swim using slow pulsations and can tolerate extreme darkness and pressure. Their glow may help them evade predators or attract prey. Due to their deep habitat, they pose little risk to humans and are of scientific interest for studies on bioluminescence and deep-sea adaptation.

16. Stygiomedusa & Deepstaria (Deep-Sea Jellies)

Classification: Scyphozoa

Habitat: Deep oceans worldwide, below 1,000 meters

Size: Up to 1 meter (3.3 ft) wide

Diet: Small fish, invertebrates

Venom: Unknown; likely mild

Stygiomedusa gigantea and Deepstaria enigmatica are rare, deep-sea jellyfish with ghostly, flowing bodies and massive oral arms instead of tentacles. They glide silently through the dark ocean, often recorded by deep-sea ROVs. Their gelatinous forms and eerie movement captivate scientists and viewers alike. Very little is known about their venom or behavior due to their extreme habitat. Their unusual appearance and rare sightings contribute to their mystery.

17. Crown Jellyfish (Coronamedusae)

Classification: Scyphozoa

Habitat: Deep-sea and midwater zones

Size: Bell up to 20 cm (8 in)

Diet: Plankton, small fish

Venom: Likely mild; unknown

Crown jellyfish have a distinctive crown-shaped bell with lobes or ridges, often appearing in shades of red or orange. They live in deeper ocean layers and are less commonly seen. Their slow, graceful movement aids in capturing prey using mucus and tentacles. Due to their inaccessibility, their venom and ecology are not well studied. These jellies are admired for their ornate structure and rarity.

18. Rhizostomae (Root-Mouthed Jellyfish – Group)

Classification: Scyphozoa

Habitat: Coastal waters worldwide

Size: Varies by species

Diet: Plankton, fish eggs

Venom: Generally mild

Rhizostomae jellyfish lack long tentacles and have fused oral arms, creating a root-like feeding structure. They include species like barrel and blubber jellies. These jellies use cilia and mucus to trap food rather than capturing with tentacles. They’re often found in shallow, warm waters and can appear in swarms. Their sting is usually not harmful to humans. Several species are commercially fished for food or collagen extraction.

19. Semaeostomeae (Order – True Jellyfish)

Classification: Scyphozoa

Habitat: Oceans worldwide

Size: Small to very large, depending on species

Diet: Zooplankton, small fish

Venom: Varies from mild to moderate

Semaeostomeae is an order containing many of the classic, bell-shaped jellyfish such as the moon jelly and sea nettle. They typically have a saucer-shaped bell with long tentacles and oral arms. Most are slow swimmers that drift with currents and capture prey with stinging cells. Some species form large seasonal blooms. Their ecological role is vital in plankton regulation and as prey for sea turtles and large fish.

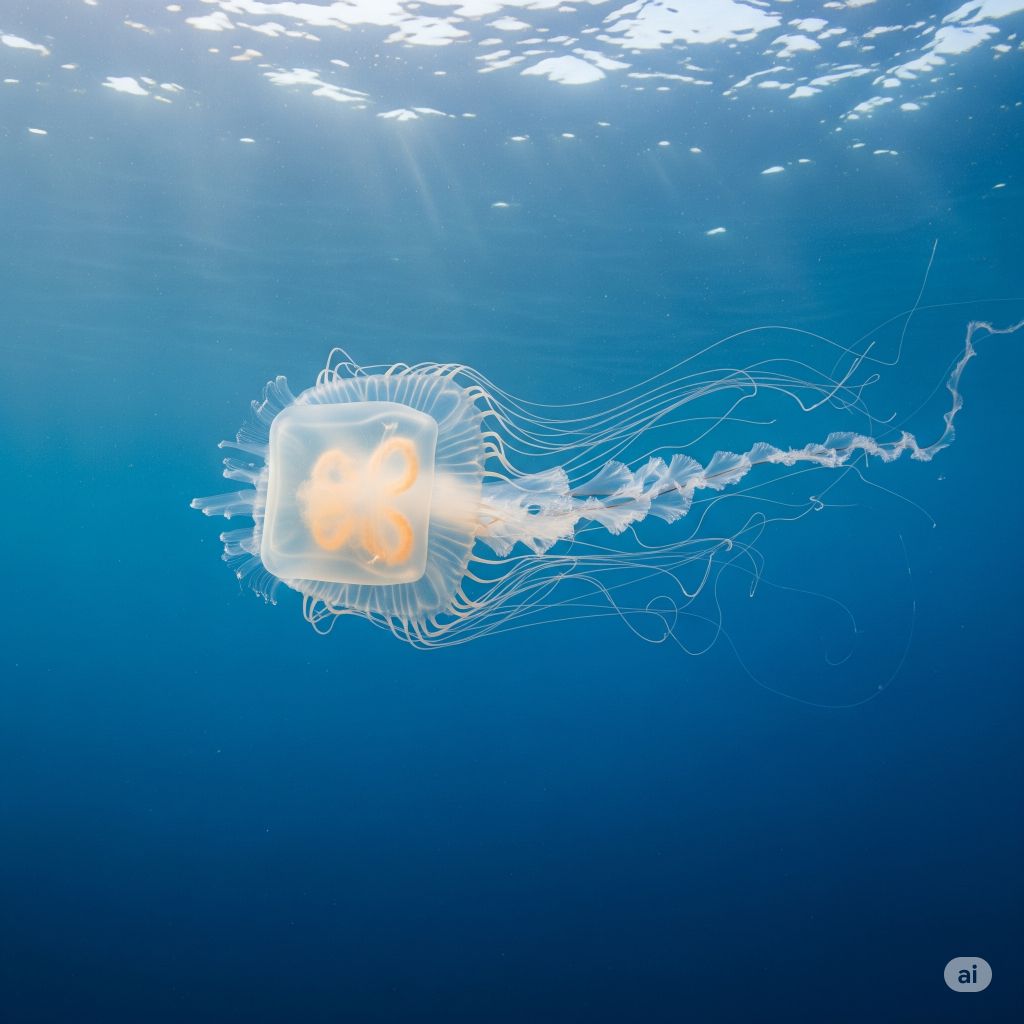

2. Cubozoa (Box Jellyfish)

Cubozoans are fast-swimming, cube-shaped jellyfish, famous for potent venom and complex eyes.

1. Australian Box Jellyfish (Chironex fleckeri)

Classification: Cubozoa

Habitat: Northern Australian and Indo-Pacific coastal waters

Size: Bell up to 30 cm (12 in); tentacles up to 3 meters (10 ft)

Diet: Small fish, crustaceans

Venom: Extremely potent; potentially deadly

The Australian box jellyfish is considered the most venomous marine animal. Its cube-shaped bell is transparent, making it hard to see in the water. It has up to 15 tentacles per corner, each covered in thousands of nematocysts capable of causing cardiac arrest in minutes. This jellyfish is a swift swimmer and uses complex eyes to navigate toward prey. Stings require immediate medical attention and antivenom. Despite its danger, it plays an important ecological role in regulating small fish populations.

2. Sea Wasps (Carybdea alata, Carybdea marsupialis)

Classification: Cubozoa

Habitat: Warm coastal waters; Caribbean, Pacific, and Mediterranean

Size: Bell up to 10 cm (4 in); tentacles up to 30 cm (12 in)

Diet: Small fish, plankton

Venom: Moderate to strong; painful stings

Sea wasps are small, cube-shaped jellyfish known for their agility and strong sting. They have four tentacles and well-developed eyes that help them track and avoid objects. Stings can cause intense pain, welts, and nausea but are rarely fatal. Carybdea marsupialis is often found in the Mediterranean, while C. alata appears in the Caribbean and Indo-Pacific. These jellies are fast swimmers and hunt actively rather than drifting, a unique trait among jellyfish.

3. Irukandji Jellyfish (Carukia barnesi, Malo kingi)

Classification: Cubozoa

Habitat: Northern Australian waters and Indo-Pacific

Size: Bell 1–2 cm (0.4–0.8 in); tentacles up to 1 meter (3.3 ft)

Diet: Larval fish, plankton

Venom: Extremely potent; can cause Irukandji syndrome

Tiny but deadly, Irukandji jellyfish are almost invisible in the water. Despite their small size, they can deliver venom that causes severe systemic symptoms known as Irukandji syndrome: muscle cramps, vomiting, anxiety, and hypertension. Some cases are life-threatening. They are rarely seen due to their transparency and small form. Swimmers in northern Australia are advised to wear stinger suits in their habitat. These jellyfish are a major focus of medical and marine research.

4. Chirodropidae (Giant Box Jellies)

Classification: Cubozoa

Habitat: Indo-Pacific, coastal tropical waters

Size: Bell up to 30 cm (12 in); tentacles several meters long

Diet: Fish, crustaceans

Venom: Highly potent; dangerous to humans

Chirodropids are a family of large box jellyfish with multiple tentacles at each bell corner. They are agile swimmers and possess clusters of eyes, enabling them to navigate toward prey. Their venom is powerful, capable of causing cardiovascular collapse. Species in this group, including Chironex yamaguchii, are responsible for severe stings in Southeast Asia and Australia. These jellyfish are typically found near coasts, especially during warmer months. Though less well-known than Chironex fleckeri, they are equally feared.

5. Tamoya ohboya (Bonaire Banded Box Jellyfish)

Classification: Cubozoa

Habitat: Caribbean Sea, especially around Bonaire and Puerto Rico

Size: Bell up to 10 cm (4 in); tentacles up to 1 meter (3.3 ft)

Diet: Small fish, crustaceans

Venom: Strong; stings cause intense pain and inflammation

Named humorously (“Oh boy!” was a researcher’s first reaction), Tamoya ohboya is a rare and vividly banded box jellyfish. Its tentacles are long and bluish, while its transparent bell may have stripes or color bands. It inhabits open coastal waters and is rarely seen near shore. Its sting causes sharp pain, swelling, and sometimes systemic symptoms. It is difficult to study due to its rarity, but sightings are occasionally reported by snorkelers and divers in the Caribbean.

3. Hydrozoa (Hydrozoan Jellyfish and Siphonophores)

This class includes both solitary and colonial forms, often much smaller and sometimes mistaken for other plankton. Some, like the Portuguese Man o’ War, are colonial and highly venomous.

Here’s the next batch: Hydrozoa (Hydrozoan Jellyfish and Siphonophores) — a class of small, often colonial jellyfish, including both harmless and venomous types. Each is ~100 words with classification, habitat, size, diet, and venom.

1. Portuguese Man o’ War (Physalia physalis)

Classification: Hydrozoa (Siphonophorae)

Habitat: Warm ocean surfaces globally

Size: Float up to 30 cm (12 in); tentacles over 30 meters (100 ft)

Diet: Fish, zooplankton

Venom: Highly venomous; painful and occasionally dangerous

Although it looks like a jellyfish, the Portuguese Man o’ War is a siphonophore—a floating colony of specialized polyps. Its gas-filled sail allows it to drift with winds and currents, while its long tentacles dangle beneath to ensnare and paralyze prey. The sting can cause severe pain, skin damage, and in rare cases, systemic reactions. It’s a common sight on beaches after storms, and warnings often follow their appearance due to sting risks. Its beautiful, balloon-like float is often iridescent with hues of blue and purple.

2. Freshwater Jellyfish (Craspedacusta sowerbyi)

Classification: Hydrozoa

Habitat: Freshwater lakes, ponds, reservoirs worldwide

Size: Bell up to 2.5 cm (1 in)

Diet: Zooplankton, tiny aquatic invertebrates

Venom: Mild; harmless to humans

Craspedacusta sowerbyi is one of the only freshwater jellyfish species. Native to the Yangtze River basin, it’s now found globally due to human-assisted dispersal. It appears seasonally and only in its medusa (jellyfish) stage during warm months. Its transparent bell pulsates gently as it captures small prey with its tentacles. Its sting is too weak to affect humans. This species alternates between polyp and medusa forms, spending much of its life as a bottom-dwelling polyp in a dormant state.

3. Obelia (Colonial Hydroid Jellies)

Classification: Hydrozoa

Habitat: Temperate and tropical oceans worldwide

Size: Colonies several centimeters long; individual polyps microscopic

Diet: Microplankton, protozoans

Venom: Very mild; not harmful to humans

Obelia is a genus of colonial hydrozoans consisting of branched, tree-like colonies of polyps. These colonies grow on submerged surfaces like rocks, shells, and seaweed. They reproduce both asexually (as polyps) and sexually (as free-swimming medusae). The medusae are tiny, bell-shaped, and often overlooked in plankton. Obelia is studied for its simple anatomy and life cycle and contributes to the planktonic food web. Its sting is too mild to affect humans.

4. Chondrophores (Porpitidae, including Velella velella)

Classification: Hydrozoa

Habitat: Warm and temperate ocean surfaces

Size: Up to 7 cm (2.8 in)

Diet: Plankton

Venom: Mild; mostly harmless to humans

Chondrophores like Velella velella, known as “by-the-wind sailors,” are colonial organisms that float on the ocean surface using a small, triangular sail. These blue, disk-shaped drifters can form massive blooms and are often stranded by wind onto beaches. Each colony consists of many specialized individuals that function as a unit. They feed on plankton using tentacles below the float. Their stings are typically too weak to affect humans, though some may cause minor irritation. Their striking appearance often surprises beachgoers during mass beachings.

5. Pink-Hearted Hydroids (Tubularia spp.)

Classification: Hydrozoa

Habitat: Shallow coastal waters, attached to rocks or pilings

Size: Stalks up to 10 cm (4 in)

Diet: Plankton

Venom: Mild; harmless to humans

Tubularia hydroids resemble tiny pink or reddish flowers, with a stalk and a cluster of tentacles forming a crown. Found in colonies attached to hard underwater surfaces, they are often mistaken for soft corals or marine plants. They capture prey with nematocysts on their tentacles. Their sting is too mild to affect humans. These hydroids do not form medusae; instead, they reproduce via budding or direct release of gametes. They are ecologically important as filter feeders and habitat providers.

6. Air Fern (Sertularia argentea)

Classification: Hydrozoa

Habitat: North Atlantic, attached to substrates like rocks or shells

Size: Colonies up to 10 cm (4 in)

Diet: Plankton, detritus

Venom: None harmful to humans

Often sold as dried “air ferns,” Sertularia argentea is actually a colonial hydrozoan, not a plant. Its stiff, branching skeleton remains after death and is sometimes dyed green and sold decoratively. In life, the colony feeds via small polyps with tentacles that filter plankton from the water. It inhabits cooler, rocky seafloors and contributes to marine biodiversity. These hydroids do not sting humans and have no medusa stage. Their hard exoskeleton provides microhabitats for tiny marine organisms.

7. Blue Button (Porpita porpita)

Classification: Hydrozoa

Habitat: Warm ocean surfaces worldwide

Size: Disc up to 3 cm (1.2 in)

Diet: Plankton

Venom: Mild; irritation possible in sensitive skin

The blue button resembles a tiny jellyfish but is actually a colonial hydrozoan. It consists of a flat, blue central float surrounded by short, radiating tentacles. It floats on the ocean surface and feeds on plankton using its stinging tentacles. Though not dangerous, contact can cause mild irritation. It drifts with currents and may wash ashore in large numbers. Blue buttons are visually striking with a vivid blue and gold color palette, often mistaken for the Portuguese Man o’ War.

4. Staurozoa (Stalked Jellyfish)

These are more sedentary, with trumpet-shaped bells and stalks used for attachment to substrates like rocks or seaweed.

1. Haliclystus antarcticus

Classification: Staurozoa

Habitat: Cold Antarctic and sub-Antarctic shallow waters, rocky substrates

Size: Up to 2 cm (0.8 in)

Diet: Tiny crustaceans, copepods

Venom: Mild; harmless to humans

Haliclystus antarcticus is a small, stalked jellyfish that anchors itself to rocks or algae using a sticky basal stalk. Its bell is trumpet-shaped with eight arms, each ending in tentacle clusters called “anchors.” These are used to trap plankton and small invertebrates. Unlike other jellyfish, it does not swim freely but may slowly contract to move short distances. It thrives in cold marine ecosystems and is an important micro-predator in Antarctic coastal zones. Its stinging cells are too weak to affect humans.

2. Haliclystus octoradiatus

Classification: Staurozoa

Habitat: Cold, shallow waters of the North Atlantic and Arctic, attached to seaweed

Size: Up to 2 cm (0.8 in)

Diet: Small planktonic animals

Venom: Mild; non-threatening to humans

This stalked jellyfish has eight symmetrical arms, giving it its species name octoradiatus. It attaches itself to algae or seagrass in tidepools or shallow coastal waters and uses its tentacles to capture prey. Its reddish or brown bell blends with seaweed, making it hard to spot. It’s seasonally visible in the UK and northern Europe. Its life cycle skips the free-swimming medusa stage, making it a curious evolutionary offshoot. Harmless to humans, it’s often studied for insights into jellyfish development.

3. Lucernaria quadricornis

Classification: Staurozoa

Habitat: Northern Atlantic and Arctic coasts, on rocks and seaweed

Size: Up to 4 cm (1.6 in)

Diet: Zooplankton, small crustaceans

Venom: Mild; not harmful to humans

Known as the four-horned stalked jellyfish, Lucernaria quadricornis has a distinctive goblet-shaped bell with four pairs of tentacles and a stalked base. It clings to underwater vegetation, often in colder tidal pools and fjords. Unlike typical jellyfish, it remains fixed for long periods, only repositioning occasionally. Its feeding tentacles sweep food into its mouth, similar to sea anemones. Its appearance and behavior are more polyp-like than medusoid, highlighting its primitive characteristics within the Cnidaria phylum.

4. Manania handi

Classification: Staurozoa

Habitat: Pacific coast of North America, especially British Columbia

Size: Around 1 cm (0.4 in)

Diet: Copepods, amphipods

Venom: Unknown; presumed mild

Manania handi is a rare, stalked jellyfish that attaches to eelgrass or rocky substrates. It features a bell with frilly lobes and long, sticky tentacles used to trap zooplankton. It’s tiny and difficult to observe in the wild, but notable for its elegant structure and behavior. Like other staurozoans, it spends its adult life attached to a surface rather than floating freely. Though its venom hasn’t been well-studied, it’s unlikely to pose any threat to humans.

5. Kishinouyea

Classification: Staurozoa

Habitat: Cold Pacific coastal regions of Japan and East Asia

Size: Estimated 1–3 cm (0.4–1.2 in)

Diet: Plankton and small benthic invertebrates

Venom: Mild or unknown

Kishinouyea is a little-known genus of stalked jellyfish, named in honor of Japanese zoologist Kamakichi Kishinouye. It shares the general staurozoan characteristics: trumpet-shaped bell, attachment stalk, and clusters of feeding tentacles. Its behavior and biology remain poorly understood due to its rarity. Found in cold, shallow waters, it attaches to rocks or algae and remains sedentary most of its life. It is not known to be harmful to humans and has not been widely studied in venom research.

6. Stylocoronella riedli

Classification: Staurozoa

Habitat: Mediterranean Sea, shallow rocky or algae-covered habitats

Size: Under 1 cm (0.4 in)

Diet: Microplankton

Venom: Unknown; likely harmless

This tiny Mediterranean stalked jellyfish is rarely seen and attaches to algae or stones in calm, shallow waters. Stylocoronella riedli has a small, tubular bell and very short tentacles. Its small size and rarity make it one of the least studied staurozoans. It likely feeds on microscopic plankton using its few tentacles, and its sting is assumed to be too weak to impact humans. It provides insights into early jellyfish evolution due to its basal position among medusozoans.

Additional Noteworthy Jellyfish

Here is a final set of Noteworthy Additional Jellyfish, each described with classification, habitat, size, diet, and venom information:

1. Flower Hat Jellyfish (Olindias formosa)

Classification: Hydrozoa

Habitat: Coastal waters of Japan, Brazil, and Argentina

Size: Bell up to 15 cm (6 in)

Diet: Small fish, crustaceans

Venom: Moderate; painful sting

This striking jellyfish has a translucent, flower-like bell ringed with fluorescent, iridescent tentacles that coil and uncoil rapidly. Mostly nocturnal, the flower hat jelly rests during the day and hunts at night. Unlike many jellyfish, it’s a strong swimmer and can actively chase prey. Its sting can be painful to humans, causing skin irritation or rashes. It is rarely encountered in large numbers, making sightings special. Its vibrant appearance has made it a popular subject in aquariums and photography.

2. Atolla Jellyfish (Atolla wyvillei)

Classification: Scyphozoa

Habitat: Deep sea, worldwide

Size: Bell up to 20 cm (8 in)

Diet: Marine snow, small invertebrates

Venom: Unknown; presumed harmless

The Atolla jellyfish is a deep-sea species famous for its bioluminescent “burglar alarm” response—emitting flashes of light to attract predators of its predator. Its bell is deep red, helping it remain nearly invisible in the dark ocean. It has a distinct trailing tentacle longer than the rest, thought to aid in feeding. Commonly observed by deep-sea submersibles, it’s adapted to extreme pressure and low temperatures. Though its sting hasn’t been extensively studied, it’s not considered a danger to humans.

3. Diplulmaris antarctica

Classification: Scyphozoa

Habitat: Southern Ocean near Antarctica

Size: Bell up to 18 cm (7 in)

Diet: Krill, zooplankton

Venom: Mild; not harmful to humans

This Antarctic jellyfish is semi-transparent with bright orange gonads visible through the bell. It’s adapted to freezing temperatures and plays a role in the polar food web by feeding on krill and being eaten by penguins and larger marine animals. Diplulmaris antarctica is often found in the upper water column of Antarctic coastal regions. Though equipped with stinging cells, its venom is not harmful to humans. Its seasonal abundance is tied to summer productivity in polar waters.

4. Golden Jellyfish (Mastigias papua etpisoni)

Classification: Scyphozoa

Habitat: Marine lakes in Palau (e.g., Jellyfish Lake)

Size: Bell up to 20 cm (8 in)

Diet: Symbiotic algae, plankton

Venom: Virtually harmless

Golden jellyfish are a subspecies of lagoon-dwelling jellyfish found in landlocked marine lakes, especially in Palau. They have evolved to lose most of their stinging ability due to lack of predators. Their golden hue comes from symbiotic algae (zooxanthellae) within their tissues, which provide energy through photosynthesis. These jellyfish migrate daily across the lake to follow the sun. Snorkeling among them is a popular tourist activity and safe due to their harmless sting. Their unique habitat and adaptation are key conservation subjects.

5. Black Sea Nettle (Chrysaora achlyos)

Classification: Scyphozoa

Habitat: Eastern Pacific, especially off California

Size: Bell up to 1 meter (3.3 ft); tentacles over 6 meters (20 ft)

Diet: Zooplankton, fish larvae

Venom: Moderate; can cause skin irritation

Rare and mysterious, the black sea nettle is a giant jellyfish with a dark purple to black bell and long, trailing tentacles. It appears sporadically in large swarms during plankton booms and then vanishes for years. Despite its size, it was only officially described in 1997. Its sting can cause painful welts but is not life-threatening. This species’ rarity, size, and deep color make it an icon of Pacific jellyfish and an indicator of changing marine conditions.

Notes on Classification

- Venomous/Dangerous: Capable of causing severe injury or death.

- Moderate/Light stinger: Causes pain or skin irritation but not usually dangerous.

- Harmless: Effects on humans are negligible or nonexistent.

Table: Quick Classification Overview

| Name (Common/Scientific) | Type | Venom Level |

|---|---|---|

| Australian Box Jellyfish (Chironex fleckeri) | Cubozoa | Dangerous/Venomous |

| Sea Wasp (Chironex yamaguchii) | Cubozoa | Dangerous/Venomous |

| Irukandji Jellyfish (Carukia barnesi and allies) | Cubozoa | Dangerous/Venomous |

| Four-handed Cube Jellyfish (Chiropsalmus quadrumanus) | Cubozoa | Dangerous/Venomous |

| Southeast Asian Sea Wasp (Chiropsalmus granchie) | Cubozoa | Dangerous/Venomous |

| Lion’s Mane Jellyfish (Cyanea capillata) | Scyphozoa | Light to Moderate |

| Mauve Stinger (Pelagia noctiluca) | Scyphozoa | Moderate |

| Flower Hat Jellyfish (Olindias formosa) | Hydrozoa | Moderate |

| Compass Jellyfish (Chrysaora hysoscella) | Scyphozoa | Light to Moderate |

| Portuguese Man o’ War (Physalia physalis) [not a true jellyfish] | Siphonophore | Dangerous/Venomous |

| Moon Jellyfish (Aurelia aurita) | Scyphozoa | Light Stinger |

| Cannonball Jellyfish (Stomolophus meleagris) | Scyphozoa | Light/Harmless |

| Crystal Jellyfish (Aequorea victoria) | Hydrozoa | Harmless |

| Fried Egg Jellyfish (Cotylorhiza tuberculata) | Scyphozoa | Harmless |

| Mushroom Jellyfish (Rhopilema verrilli) | Scyphozoa | Mild |

| Black Sea Nettle (Chrysaora achlyos) | Scyphozoa | Light Stinger |

| Cauliflower Jellyfish (Cephea cephea) | Scyphozoa | Mild |

| Upside-down Jellyfish (Cassiopea spp.) | Scyphozoa | Mild |

| Many-ribbed Jellyfish (Aequorea forskalea) | Hydrozoa | Harmless |

| Blue Blubber Jellyfish (Catostylus mosaicus) | Scyphozoa | Light Stinger |

| Immortal Jellyfish (Turritopsis dohrnii) | Hydrozoa | Harmless |

| Comb Jellies (Ctenophora) | Ctenophora | Harmless |

Final Thought

Jellyfish represent an extraordinary organic diversity—a spectrum from the beautiful, ethereal, and harmless to the stunningly swift and deadly. Always consult updated guides when swimming in jellyfish zones, and never handle live or beached specimens, even in seemingly “safe” regions. Their role in marine food webs and human culture only grows as we learn more about these mesmerizing creatures.

Citations:

https://study.com/academy/lesson/types-of-jellyfish.html

https://ocean.si.edu/ocean-life/invertebrates/how-do-jellyfish-sting

https://www.britannica.com/animal/jellyfish

https://ufhealth.org/conditions-and-treatments/jellyfish-stings

94% of pet owners say their animal pal makes them smile more than once a day. In 2007, I realized that I was made for saving Animals. My father is a Vet, and I think every pet deserves one. I started this blog, “InPetCare”, in 2019 with my father to enlighten a wider audience.