Nature is not gentle. Every day, animals face threats from predators, competitors, and environmental dangers. To survive, species have evolved astonishing defense strategies—some bizarre, some brilliant, and some almost unbelievable. While claws and teeth are common tools, many animals rely on highly specialized mechanisms that go far beyond brute force.

Below are the animals with truly unusual defense mechanisms, explained in detail—how they work, why they evolved, and what makes them so effective.

Post Contents

- Nature’s Most Interesting Animal Defence Mechanisms

- 1. Spines & Thorns

- 2. Liquid Secretions

- 3. Shape

- 4. Colours & Camouflage

- 5. Shield as Defence

- 6. Gaseous Secretions

- 7. Detaching of Body Parts

- 8. Majority (Safety in Numbers)

- 9. Size

- 10. Mimicry

- 31 Unusual Animal Defense Mechanisms & Why They Matter

- 1.Bombardier Beetle – Chemical Explosion Defense

- 2. Texas Horned Lizard – Blood-Squirting Eyes

- 3. Hagfish – Instant Slime Cloud

- 4. Sea Cucumber – Ejecting Internal Organs

- 5. Pangolin – Living Armor Ball

- 6. Mimic Octopus – Shape-Shifting Illusionist

- 7. Opossum – Playing Dead (Thanatosis)

- 8. Archerfish – Precision Water Blasts

- 9. African Hairy Frog – Breaking Its Own Bones

- 10. Wood Frog – Freezing Solid

- 11. Skunk – Chemical Spray Accuracy

- 12. Pufferfish – Rapid Inflation and Toxins

- 13. Malaysian Exploding Ant – Self-Destructive Defense

- 14. Electric Eel – High-Voltage Shock

- 15. Cuttlefish — Color-Changing Defense

- 16. Porcupine — Quill Release & Deterrence

- 17. Stink Bug — Odor Release

- 18. Squid — Ink Cloud Defense

- 19. Glass Frog — Transparency Trait

- 20. Anaconda — Constriction Defense

- 21. Iberian Ribbed Newts — Turn Their Ribs Into Defensive Spikes

- 22. Pygmy Sperm Whales — Release Clouds of Defensive Waste

- 23. Slow Lorises — Raise Their Arms and Mimic Venomous Cobras

- 24. Exploding Ants — Sacrifice Themselves to Stop Enemies

- 25. Termites — Detonate Toxic Goo From Built-In Chemical Sacs

- 26. Northern Fulmars — Weaponize Vomit Against Predators

- 27. Motyxia Millipedes — Glow and Secrete Cyanide

- 28. Flying Fish — Glide Through the Air to Escape Ocean Predators

- 29. Boxer Crabs — Wield Venomous Sea Anemones Like Boxing Gloves

- 30. Dynastor Butterfly Caterpillars — Transform Into Snake Impersonators

- 🌿 Quick Summary

- Why Unusual Defenses Evolve

- Final Thoughts

Nature’s Most Interesting Animal Defence Mechanisms

Survival in the wild is a constant challenge. Animals face threats from predators, environmental changes, and competition for resources. Over millions of years, evolution has equipped species with fascinating defence mechanisms designed to help them avoid danger, deter attackers, or escape when threatened. Some rely on physical weapons, while others use deception, teamwork, or chemical warfare.

These strategies are not random — they are finely tuned adaptations that increase an animal’s chances of survival and reproduction. From creatures that release toxic chemicals to those that disguise themselves as something entirely different, nature offers countless examples of ingenuity.

Let’s explore ten of the most interesting animal defence mechanisms, along with real-world examples and explanations of how they work.

1. Spines & Thorns

One of the simplest yet most effective defence strategies is the use of sharp physical structures such as spines, quills, or thorn-like projections. These features discourage predators by making an attack painful or even dangerous.

A classic example is the porcupine, whose body is covered in thousands of sharp quills. Contrary to popular belief, porcupines cannot shoot their quills, but the barbed tips detach easily when touched. Once embedded in a predator’s skin, they can cause infections or severe discomfort, often teaching attackers to avoid porcupines in the future.

Another excellent example is the hedgehog. When threatened, it curls into a tight ball, exposing only its spines. This posture protects vulnerable areas such as the face and belly. Many predators simply give up because there is no safe way to bite.

In marine environments, the sea urchin uses long, sometimes venomous spines to ward off fish. Some species even possess toxins that amplify the deterrent effect.

Spines work because they increase the cost of predation. Predators prefer easy meals — if an animal looks painful to eat, it is often ignored in favor of safer prey.

2. Liquid Secretions

Some animals defend themselves by releasing liquids that are toxic, foul-smelling, sticky, or irritating. This chemical defence can confuse predators long enough for the prey to escape.

The most famous example is the skunk, which sprays a sulfur-containing liquid from specialized glands. The smell is so strong it can linger for days, and it can temporarily blind predators if it enters the eyes. Many animals learn quickly to recognize the skunk’s warning posture and stay away.

Another remarkable species is the bombardier beetle. When threatened, it ejects a boiling chemical spray from its abdomen. The reaction inside its body mixes compounds that create a hot, noxious burst capable of startling frogs, birds, and even spiders.

The hagfish offers a different approach. When attacked, it releases massive amounts of slime that clog a predator’s gills, forcing the attacker to retreat.

Liquid secretions are effective because they create an immediate sensory overload — smell, heat, or irritation — giving prey a valuable chance to escape.

3. Shape

Sometimes survival depends simply on not being recognized as food. Many animals evolve body shapes that resemble harmless objects in their environment.

The stick insect is a master of this strategy. Its long, thin body looks almost identical to a twig. Some species even sway gently, mimicking branches moving in the wind.

Similarly, the leaf-tailed gecko has a flattened tail that looks like a decaying leaf, complete with vein-like patterns. During the day, it rests motionless against tree bark, becoming nearly invisible.

In the ocean, the seahorse blends into coral and sea grass with its upright posture and irregular outline. Predators scanning for typical fish shapes often overlook it.

Shape-based defence works because predators rely heavily on visual cues. If prey doesn’t match the mental image of “food,” it may never be detected.

4. Colours & Camouflage

Camouflage is one of nature’s most sophisticated defence mechanisms. By blending into surroundings, animals avoid detection entirely.

The chameleon is famous for changing color, though it often does so for communication and temperature regulation as well. Still, its ability to match nearby hues helps it stay hidden.

The snowshoe hare changes fur color seasonally — brown in summer and white in winter — ensuring year-round concealment.

Meanwhile, the octopus can alter both color and skin texture within seconds, imitating rocks, sand, or coral. This rapid transformation makes it incredibly difficult for predators to spot.

Camouflage reduces the need for confrontation. If predators never see their prey, they cannot attack.

5. Shield as Defence

Some animals carry built-in armor that acts as a protective shield.

The turtle is perhaps the best-known example. Its hard shell protects vital organs, allowing it to withdraw completely when threatened. Few predators can crack this natural fortress.

The armadillo relies on bony plates covering its body. Certain species can roll into a ball, leaving predators with nothing but tough armor to bite.

Even insects use this tactic — the tortoise beetle has a transparent, shield-like structure that covers its delicate wings.

Armor works by increasing survival during an attack. Instead of fleeing, these animals rely on durability.

6. Gaseous Secretions

Some species weaponize gas to deter predators.

The bombardier beetle, mentioned earlier, produces not only liquid spray but also a hot vapor that can irritate skin and eyes.

Termites provide another fascinating example. Certain soldier termites release defensive chemicals that evaporate quickly, forming a repellent cloud around the colony.

These gaseous defences are particularly useful in confined spaces like tunnels or burrows, where predators cannot easily avoid the fumes.

Gas-based protection creates distance — attackers often retreat before making contact.

7. Detaching of Body Parts

Autotomy, or self-amputation, is a dramatic but effective escape strategy.

The lizard is famous for dropping its tail when grabbed. The detached tail continues to wiggle, distracting the predator while the lizard escapes. Although regrowing the tail requires energy, survival makes the cost worthwhile.

Some sea stars can lose an arm and later regenerate it. In certain cases, the lost limb can even grow into a new individual.

This strategy works because it redirects the predator’s attention. Movement triggers hunting instincts, so the discarded body part becomes the focus instead of the escaping animal.

8. Majority (Safety in Numbers)

Many animals rely on group living to reduce individual risk — a strategy often called the “dilution effect.”

A herd of wildebeest on the African savanna demonstrates this perfectly. When thousands move together, a predator has difficulty targeting one animal.

Schools of fish confuse attackers through synchronized motion. Predators struggle to focus on a single target when dozens change direction simultaneously.

Bird flocks use similar tactics, forming swirling patterns that disorient hunters.

Group defence works because it lowers the probability that any one individual will be captured.

9. Size

Sometimes the best defence is simply being too big to attack.

The elephant has few natural predators due to its enormous size and strength. Even lions rarely attempt to hunt healthy adults.

The blue whale, the largest animal ever known, faces virtually no predation once fully grown.

Large animals often pair size with intimidation — stomping, charging, or vocalizing loudly to scare threats away.

Size acts as a deterrent by increasing the danger for predators. Hunting large prey can result in serious injury, so most predators avoid the risk.

10. Mimicry

Mimicry is one of evolution’s cleverest tricks — looking like something more dangerous than you actually are.

The harmless king snake resembles the venomous coral snake, causing predators to think twice before attacking.

The hoverfly mimics the black-and-yellow pattern of wasps despite lacking a stinger.

Some octopuses can imitate multiple species, including venomous lionfish, altering both posture and movement.

Mimicry succeeds because predators rely on past experiences. If a pattern signals danger, they avoid it — even when the threat is fake.

31 Unusual Animal Defense Mechanisms & Why They Matter

Animal defence strategies do more than protect individuals; they shape entire ecosystems. Predators adapt to overcome prey defences, while prey continue evolving stronger protections — a process known as the evolutionary arms race.

These mechanisms also highlight biodiversity’s importance. Each adaptation represents millions of years of natural experimentation. When species disappear, we lose unique biological solutions that may never evolve again.

Human activity — habitat destruction, pollution, and climate change — increasingly threatens these delicate survival systems. Protecting wildlife ensures these remarkable strategies continue to inspire scientific discovery.

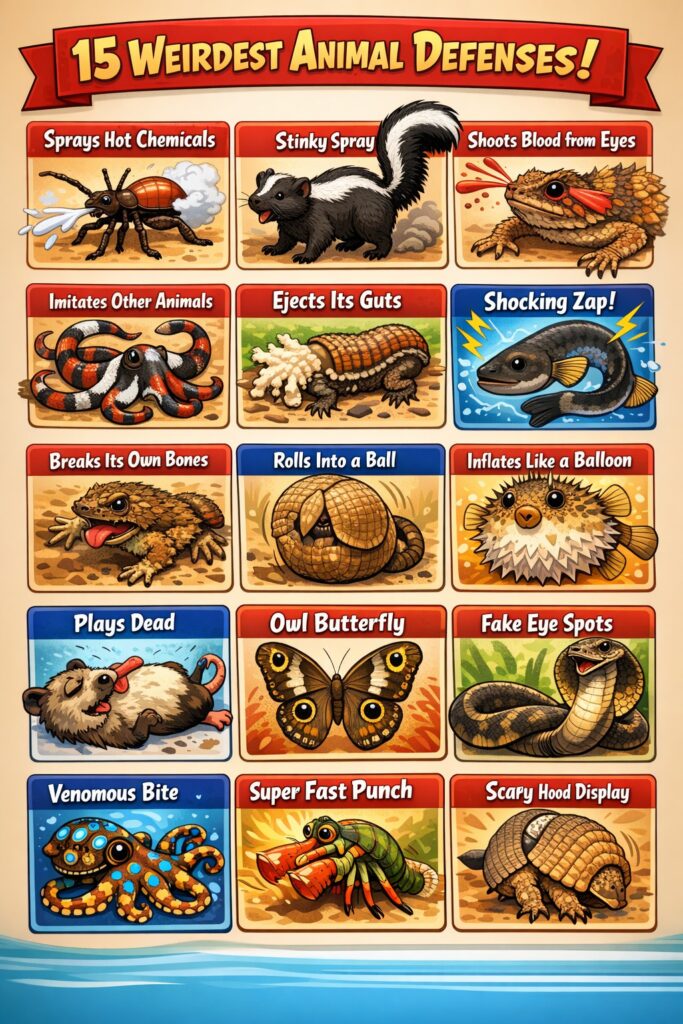

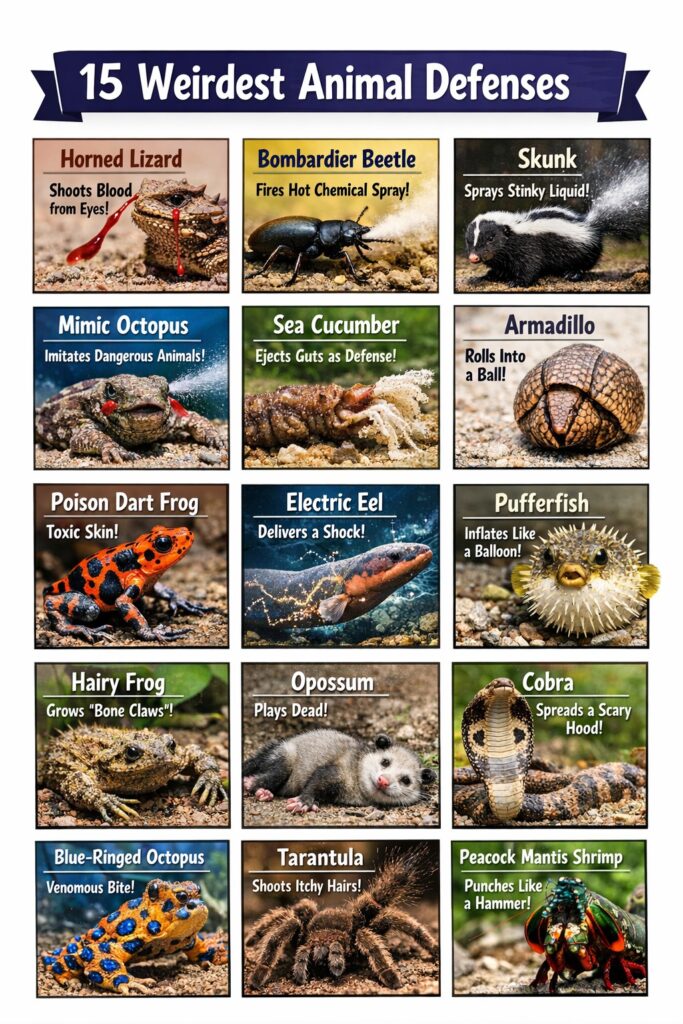

1.Bombardier Beetle – Chemical Explosion Defense

The bombardier beetle has one of the most dramatic defenses in the insect world. When threatened, it sprays a boiling, noxious chemical mixture from its abdomen.

Inside specialized abdominal chambers, the beetle stores hydroquinones and hydrogen peroxide separately. When danger strikes, these chemicals mix in a reaction chamber containing enzymes. The reaction rapidly heats to nearly 100°C (212°F), producing an explosive spray that shoots out in rapid pulses.

This chemical blast:

- Irritates predators’ skin and eyes

- Produces a loud popping sound

- Can be aimed with surprising accuracy

Few predators risk attacking a creature capable of firing a boiling chemical weapon.

2. Texas Horned Lizard – Blood-Squirting Eyes

The Texas horned lizard has an unforgettable defense: it can squirt blood from the corners of its eyes.

When threatened by canids (like foxes or coyotes), the lizard increases blood pressure in vessels around the eyes until they rupture. Blood shoots up to several feet outward.

Why is this effective?

- The blood tastes foul to mammalian predators

- It confuses and startles attackers

- It allows the lizard time to escape

This defense is rarely used—it’s a last resort when camouflage and puffing up fail.

3. Hagfish – Instant Slime Cloud

Hagfish defend themselves by releasing massive amounts of slime into the water when attacked.

Specialized glands along their body produce protein threads and mucus. When mixed with seawater, the slime expands instantly into a thick, sticky mass that can clog a predator’s gills.

The result:

- Fish attempting to bite the hagfish may suffocate

- Predators often release them immediately

- The slime deters future attacks

Remarkably, hagfish can tie themselves into knots to wipe slime off their own bodies afterward.

4. Sea Cucumber – Ejecting Internal Organs

Sea cucumbers have one of the most extreme defense mechanisms in the ocean: they eject their internal organs.

When threatened, some species forcefully expel sticky tubules—or even parts of their digestive tract—through their anus. These sticky structures entangle predators.

Afterward:

- The sea cucumber regenerates lost organs

- The predator is distracted or immobilized

- Escape becomes possible

Regeneration may take weeks, but survival makes the sacrifice worthwhile.

5. Pangolin – Living Armor Ball

Pangolins are covered in overlapping keratin scales—similar to human fingernails.

When threatened, they:

- Curl into a tight armored ball

- Protect their vulnerable belly

- Use powerful tail muscles to reinforce the shield

Predators like lions struggle to break through this natural armor. Unfortunately, this same defense makes pangolins vulnerable to human poachers, who can easily pick them up when curled.

6. Mimic Octopus – Shape-Shifting Illusionist

The mimic octopus can impersonate multiple dangerous marine animals.

By changing skin color, texture, and posture, it mimics:

- Lionfish

- Sea snakes

- Flatfish

- Jellyfish

It selects which species to mimic depending on the predator it faces. This intelligent defensive mimicry reduces the need for physical confrontation.

7. Opossum – Playing Dead (Thanatosis)

The Virginia opossum uses a dramatic form of defensive deception: playing dead.

When severely threatened:

- It collapses onto its side

- Its mouth hangs open

- It secretes foul-smelling fluid

- Its heart rate slows dramatically

Predators that prefer live prey often lose interest in what appears to be a dead animal. This involuntary response can last several minutes to hours.

8. Archerfish – Precision Water Blasts

While primarily a hunting technique, the archerfish’s ability to shoot jets of water also serves as defense.

When threatened near the water’s surface:

- It can knock small threats off perches

- Create splash disturbances

- Deter insects or small predators

The fish uses complex calculations to compensate for light refraction when aiming.

9. African Hairy Frog – Breaking Its Own Bones

Also known as the “horror frog,” this amphibian has retractable claws unlike any other frog species.

When threatened:

- It deliberately breaks toe bones

- The broken bone tips puncture through skin

- They form sharp claws

Once danger passes, tissue heals and bones retract. It is one of the few known vertebrates to weaponize its own skeleton in this way.

Researchers suspect strong collagen fibers help keep the bone fragments aligned so they can return to their original position. While painful-looking, this adaptation provides an emergency weapon when escape isn’t possible.

The hairy frog reminds us that evolution sometimes favors extreme solutions, especially in environments where hesitation could mean becoming someone else’s meal.

10. Wood Frog – Freezing Solid

The wood frog survives cold temperatures by freezing solid during winter.

Up to 70% of its body water freezes. Its heart stops. It appears dead.

However:

- Glucose acts as a cryoprotectant

- Ice forms only between cells

- Organs remain intact

When temperatures rise, the frog thaws and resumes normal activity. Freezing prevents predators from detecting movement and allows survival in extreme climates.

11. Skunk – Chemical Spray Accuracy

Skunks are famous for their powerful spray, but what makes it unusual is their aim and control.

They can:

- Spray up to 10 feet

- Adjust the intensity

- Aim precisely at eyes

The sulfur-based chemicals cause temporary blindness and intense irritation, giving the skunk time to escape.

12. Pufferfish – Rapid Inflation and Toxins

Pufferfish inflate by swallowing water (or air) into elastic stomachs.

This causes:

- Body size to double or triple

- Spines to protrude

- Difficulty for predators to swallow them

Many species also contain tetrodotoxin, a potent neurotoxin that deters predators from attempting a second attack.

13. Malaysian Exploding Ant – Self-Destructive Defense

This ant performs autothysis—a suicidal explosion.

When threatened:

- It contracts abdominal muscles

- Internal glands rupture

- Sticky, toxic fluid sprays outward

The ant dies, but the predator is immobilized or repelled. It is a colony-level survival strategy.

14. Electric Eel – High-Voltage Shock

Electric eels generate powerful electric discharges using specialized cells called electrocytes.

They can:

- Emit shocks exceeding 600 volts

- Stun predators

- Immobilize prey

Recent studies show electric eels can leap partially out of water to deliver shocks directly to threats touching the surface.

Got it — here’s a clear, concise breakdown of each defense mechanism you listed, explained biologically and behaviorally:

15. Cuttlefish — Color-Changing Defense

The uses specialized skin cells called chromatophores, iridophores, and leucophores to change color and texture in milliseconds.

How it defends them:

- Instantly camouflages to match sand, coral, or rocks

- Flashes high-contrast warning patterns to confuse predators

- Mimics dangerous animals in some situations

This rapid visual transformation helps cuttlefish avoid detection or startle attackers long enough to escape.

16. Porcupine — Quill Release & Deterrence

The is covered in sharp keratin quills that act as a physical barrier.

Defense strategy:

- Raises quills when threatened

- Charges backward into predators

- Quills detach easily and embed painfully

Contrary to myth, porcupines don’t shoot quills—but contact alone is enough to seriously injure attackers.

17. Stink Bug — Odor Release

The releases a strong-smelling chemical from glands in its thorax.

Why it works:

- Odor tastes bitter and unpleasant

- Startles predators

- Signals toxicity or inedibility

This chemical defense makes birds and reptiles quickly learn to avoid stink bugs.

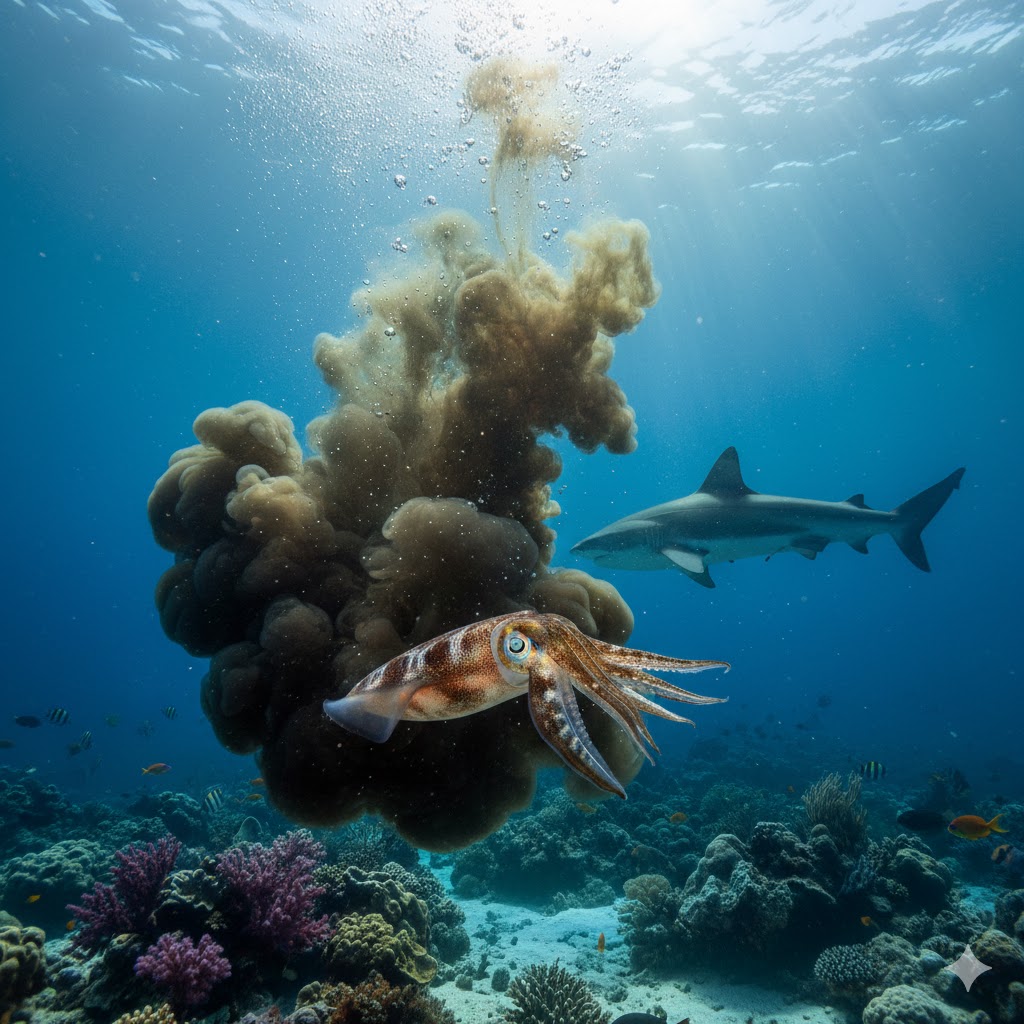

18. Squid — Ink Cloud Defense

The ejects a cloud of dark ink when threatened.

The ink serves multiple purposes:

- Creates a visual smokescreen

- Contains tyrosinase, which irritates predator senses

- Sometimes forms a “pseudo-body” decoy

While predators attack the ink blob, the squid jets away.

19. Glass Frog — Transparency Trait

The has translucent skin, allowing internal organs to be partially visible.

Defensive advantage:

- Blends into leaves by reducing shadow

- Makes body outline harder to detect

- Recently discovered ability to hide red blood cells in the liver while resting

This biological transparency dramatically lowers visibility to predators.

20. Anaconda — Constriction Defense

The relies on immense muscular power rather than venom.

How constriction works defensively:

- Wraps coils around threats

- Applies pressure that restricts blood flow

- Quickly incapacitates attackers

Although mainly a hunting method, constriction also serves as a powerful deterrent against large predators.

21. Iberian Ribbed Newts — Turn Their Ribs Into Defensive Spikes

The Iberian ribbed newt has one of the most shocking defence mechanisms in the animal kingdom — it can push its own ribs through its skin to create sharp spikes. When threatened, the newt contracts special muscles that force the rib tips outward. These ribs pierce toxin-coated skin glands, effectively turning each spike into a venom-delivery system.

Surprisingly, this process does not seriously harm the newt. Its skin heals quickly, showing remarkable regenerative abilities. Predators that attempt to bite often receive painful punctures along with toxic exposure, quickly learning to avoid the species.

This strategy is rare among vertebrates because it combines mechanical injury with chemical defence. Rather than fleeing, the Iberian ribbed newt transforms its entire body into a weapon — proving that sometimes the best shield is becoming dangerous to touch.

22. Pygmy Sperm Whales — Release Clouds of Defensive Waste

Instead of fighting predators, pygmy sperm whales rely on a bizarre but effective escape tactic — they eject large clouds of reddish-brown intestinal fluid into the water. This substance creates a thick, murky barrier that blocks visibility, much like a squid’s ink cloud.

When startled, the whale expels the liquid and quickly swims away while the predator struggles to see through the floating plume. Sharks, one of their primary threats, depend heavily on vision during the final moments of a hunt, so this sudden visual disruption can mean the difference between life and death.

Scientists believe the fluid may also confuse predators chemically by masking the whale’s scent trail. Though it may sound unpleasant, this strategy demonstrates a simple survival principle: if an attacker can’t see you, it can’t catch you.

23. Slow Lorises — Raise Their Arms and Mimic Venomous Cobras

Slow lorises may appear adorable, but they possess a surprisingly intimidating defence display. When threatened, they lift their arms above their heads and sway — a posture strikingly similar to a cobra preparing to strike. This mimicry can startle predators long enough for the loris to escape.

Even more fascinating, slow lorises are one of the few venomous mammals. They lick toxin-producing glands on their arms, mixing the secretion with saliva to deliver a painful bite. The venom can cause severe allergic reactions in attackers.

Their slow movements might seem like a disadvantage, but this deceptive display reduces the need for speed. By combining visual intimidation with genuine toxicity, slow lorises blur the line between mimicry and real danger — proving that appearances can be powerfully misleading.

24. Exploding Ants — Sacrifice Themselves to Stop Enemies

Certain species of ants defend their colonies through a dramatic act known as autothysis — essentially self-explosion. When confronted by invading insects, worker ants contract their abdominal muscles until their body ruptures, spraying sticky, toxic fluid onto the attacker.

This substance can immobilize or kill enemies while also acting as a chemical alarm signal for nearby colony members. Though the individual ant dies, the sacrifice protects the queen and thousands of relatives, ensuring the survival of shared genes.

This behaviour highlights the extreme cooperation found in social insects. In ant societies, the colony functions almost like a single organism, where individual loss is acceptable if it prevents greater harm.

It is one of nature’s clearest examples of altruism shaped by evolution.

25. Termites — Detonate Toxic Goo From Built-In Chemical Sacs

Some termite soldiers function as living chemical weapons. Their bodies develop specialized sacs filled with sticky, toxic secretions. When attackers breach the nest, these termites rupture the sacs, releasing glue-like substances that trap predators such as ants.

The fluid can harden quickly, immobilizing the threat while toxins weaken it. Often, the termite dies in the process — another example of self-sacrifice for colony defence.

Because termite nests house millions of vulnerable individuals, this explosive protection is highly effective. It creates a defensive barrier that invaders must struggle through, buying precious time for the colony.

Such adaptations demonstrate how social insects prioritize collective survival over individual life, evolving strategies that would seem extreme in solitary animals.

26. Northern Fulmars — Weaponize Vomit Against Predators

Northern fulmars protect their nests with a stomach oil that doubles as a projectile weapon. When threatened, chicks and adults accurately spit this oily substance at predators from several feet away.

The oil is incredibly foul-smelling and sticky. When it coats a bird’s feathers, it destroys their waterproofing and insulation, often preventing flight. Many attackers are forced to retreat to clean themselves, abandoning the hunt entirely.

Producing this oil requires energy, so fulmars deploy it carefully — usually when eggs or chicks are at risk. The strategy is especially effective against aerial predators that depend on feather condition for survival.

By turning digestion into defence, fulmars prove that sometimes the best weapon is already inside you.

27. Motyxia Millipedes — Glow and Secrete Cyanide

Motyxia millipedes combine two warning systems: they glow in the dark and release cyanide-based toxins. Their faint bioluminescence acts as a nighttime signal to predators that they are dangerous to eat.

If ignored, the millipede can ooze chemicals capable of causing irritation or poisoning small attackers. Studies suggest predators quickly learn to associate the glow with an unpleasant experience.

Interestingly, the light is not meant to illuminate surroundings but to advertise toxicity — a strategy known as aposematism. Rather than hiding, these millipedes boldly announce their defenses.

This approach saves energy otherwise spent on fleeing and reduces repeated attacks. In the darkness of their habitat, glowing becomes less of a vulnerability and more of a highly visible “do not touch” sign.

28. Flying Fish — Glide Through the Air to Escape Ocean Predators

Flying fish don’t truly fly, but their powerful escape leaps are nothing short of spectacular. When chased, they burst from the water at speeds exceeding 35 miles per hour and spread wing-like pectoral fins to glide above the surface.

Some species can remain airborne for hundreds of feet, using updrafts created by waves to extend their journey. This aerial detour often confuses fast-swimming predators like tuna and mahi-mahi, which suddenly lose track of their target.

However, the maneuver carries risks — seabirds may attack from above. Still, the strategy dramatically improves survival odds by shifting the chase into an entirely different environment.

Flying fish demonstrate an important evolutionary lesson: sometimes escaping danger requires breaking the usual boundaries of your world.

29. Boxer Crabs — Wield Venomous Sea Anemones Like Boxing Gloves

Boxer crabs defend themselves in a truly unique way — they hold tiny sea anemones in their claws and brandish them like stinging pom-poms. These anemones possess venomous cells that deliver painful stings to would-be predators.

If one anemone is lost, the crab can split the remaining one into two, essentially cloning its weapon. In return, the anemones receive mobility and access to food scraps, forming a mutually beneficial partnership.

This relationship is a striking example of symbiosis used for defence. Instead of evolving its own toxin, the crab recruits another species to do the job.

By outsourcing protection, boxer crabs reveal how cooperation in nature can be just as powerful as physical adaptation.

30. Dynastor Butterfly Caterpillars — Transform Into Snake Impersonators

The larvae of the Dynastor butterfly rely on theatrical deception. When disturbed, the caterpillar retracts its head and inflates body segments to resemble the triangular head of a snake. Some even display eye-like markings that enhance the illusion.

To heighten the performance, the caterpillar may jerk its body in a striking motion, convincing predators they are facing a reptile rather than a defenseless insect. Birds, which instinctively avoid snakes, often retreat immediately.

This defence requires no venom or armor — only convincing visual mimicry. By exploiting predator instincts, the caterpillar avoids physical confrontation altogether.

It’s a perfect reminder that in nature, survival doesn’t always go to the strongest — sometimes it goes to the best actor.

🌿 Quick Summary

Each of these animals demonstrates a different survival strategy:

- Visual deception (cuttlefish, glass frog)

- Chemical deterrence (stink bug, squid)

- Physical weapons (porcupine, anaconda)

Nature doesn’t rely on one solution—evolution favors whatever keeps the species alive.

Why Unusual Defenses Evolve

Unusual defenses evolve when:

- Predators adapt to common defenses

- Environments create new survival pressures

- Cooperation or sacrifice increases survival odds

Many of these strategies may seem extreme, but they are highly efficient in context.

Nature rewards innovation.

Final Thoughts

The animal kingdom is filled with astonishing survival tactics. From blood-squirting lizards to self-exploding ants, these defenses demonstrate that evolution doesn’t always choose brute strength—it often favors creativity.

Each of these animals represents millions of years of adaptation shaped by predator-prey dynamics. The result? Some of the strangest, most effective survival tools on Earth.

94% of pet owners say their animal pal makes them smile more than once a day. In 2007, I realized that I was made for saving Animals. My father is a Vet, and I think every pet deserves one. I started this blog, “InPetCare”, in 2019 with my father to enlighten a wider audience.